By Wong Pei Chi

In commemorating this 101st anniversary of International Women’s Day, let us remind ourselves that this Day came about historically to mark the expansion of women’s choices and rights, including the right to protection against discrimination.

The first International Women’s Day, commemorated on 19 March 1911, was marked by public rallies in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland calling for the limited choices then available to women to be expanded to the right to vote, the right to work, and protection against discrimination.

The first International Women’s Day, commemorated on 19 March 1911, was marked by public rallies in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland calling for the limited choices then available to women to be expanded to the right to vote, the right to work, and protection against discrimination.

Living in Singapore in 2013, we are often told how fortunate we are to have more choices than women of previous generations had available to them. However, we need to ask what these choices include. Here, I argue that there is a paradox of “choice” and explore how the way we think about “choice” limits the possibilities for social change that we can envision and enact.

One example of this paradox of choice that does not leave much to be chosen is the ongoing debate on “work-life balance”. Supporters laud work-life balance proposals for going some way to redressing the discrimination that women face, partly due to the social norm that we are disproportionately likely to be the primary caregivers in the home, which limits our choices in the workplace.

Detractors say that women who choose to have children should not complain about the consequences of that choice, conveniently forgetting that a male partner would have been involved at some stage in the process, and that society does not expect him to bear the responsibilities of childcare nor the social approbation that accompanies asking for support of those responsibilities. So why is it that only one party has to bear the consequences of what is supposedly a collective choice?

The way we talk about “choice” in the context of work and family decisions mirrors the way we talk about consumer choice, as if we all have the same choices laid out in front of us, and merely need to choose the best one. Individuals are expected to bear negative consequences arising from miscalculated choices or unforeseen changes in our circumstances.

More fundamentally, even the lack of good choices available is somehow our responsibility. At the same time, social engineering penalises some people for their social status, which is framed as a “choice”. The assertion that we “chose” to be in such an undesirable situation becomes the justification for not providing social support to individuals.

For example, it is common for people to resent a female co-worker who has just given birth for taking a few months of maternity leave. She is seen to be leaving others to carry on her work while she cares for her child, as if this is a “lifestyle” feature to be enjoyed at others’ expense.

For example, it is common for people to resent a female co-worker who has just given birth for taking a few months of maternity leave. She is seen to be leaving others to carry on her work while she cares for her child, as if this is a “lifestyle” feature to be enjoyed at others’ expense.

The alternative of quitting work altogether results in difficulties for many women when they try to rejoin the workforce. What is hidden in this discourse is that the dilemma between childbearing and sustaining formal employment that confronts many women, is not seen as an issue that men who benefit from having children have to contend with.

Why is it almost unheard of for fathers to take significant time off work, or to quit work, to care for their newborn children, so that mothers can return to work sooner? Rigid gender roles limit the options that we can envision for ourselves and each other.

Hence, we see that the paradox of “choice” arises because of the conflation of two meanings within the word “choice”. There is free will, the ability to create new alternatives and shape the world around us to suit us, and then there is agency, the ability to choose among existing options, of which none may be desirable.

For most of us, what we have is the latter and not the former, which is why “option” is a better word to use for this Hobson’s choice than the word “choice”, implying free choice.

At the same time, our current social norms invisibilise and devalue family structures which include unwed parents, same-sex couples, adoption, families where members are not related by blood, and so on.

When our conception of “family” is so narrow, women who do not exercise the option to become heterosexually married and have children for various reasons are seen as irresponsible and selfish, and women who already consider themselves part of a family, albeit unrecognised, are left out.

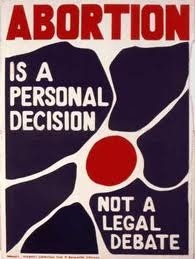

Women’s exercise of reproductive agency is fraught with social penalties revolving around this idea of “choice:. The seductive myth that is “choice” renders us responsible for social circumstances beyond our control.

Women’s exercise of reproductive agency is fraught with social penalties revolving around this idea of “choice:. The seductive myth that is “choice” renders us responsible for social circumstances beyond our control.

An example of these social circumstances is the way that the Singapore government, in expending much effort and money to get women to have children, has marked this option as preferable over others and accorded incentives for it. On the other hand, six out of ten companies resist implementing work-life strategies which would expand women’s options beyond the stark dilemma between caring for children and keeping their jobs.

In this context, women are compelled to exercise their limited options between the “choice” of the government and the “choice” of most employers. If they go with the government’s “choice”, they may find themselves penalised by an unsupportive employer’s “choice”. Conversely, if they go with an unsupportive employer’s “choice”, this would reduce the relevance of the government’s “choice”.

In either case, women are constrained to picking what has been pre-selected for them by others.

Since we are dealing, not so much with women’s own “choices”, but with the “choices” that have been made for them, we need to question the motivations underlying the latter. Although the State designates childbearing and caregiving as almost exclusively the responsibility of women, it simultaneously narrows its already limited recognition of the value of these activities to the context of heterosexually married women who hold formal jobs.

It is clear from the example of the Marriage and Parenthood Package that not all options are equally available to all women. The payouts and benefits are only available to married women. Furthermore, because these benefits are either explicitly restricted to working mothers or disbursed in the form of a reduced maid levy or tax reliefs, these disproportionately benefit women who work and earn higher taxable income.

We need to question why certain women should be discriminated against on the basis of marital and employment status. In a competitive society, rewarding some people on the basis of social status effectively penalises those who do not meet the criteria. It is revealing that this bias is justified by policy makers as rewarding particular choices – for example, working mothers who “made a choice to work”, to quote Minister of State Amy Khor.

There seems to be no recognition that some other mothers do not have the luxury of this “choice”, for example, because what they can earn working outside their home may not be enough for them to hire a foreign domestic worker, so as to claim tax relief for the levy paid for this worker, which is a perk that rewards the “choice” of being a working mother.

The marital status and employment criteria, as well as the tax-based nature of the Marriage and Parenthood Package, have serious implications on existing class and ethnic divisions in Singapore.

Our place in the social hierarchy influences just how many options we have. Women at the top of the social hierarchy will tend to have more options by virtue of our social location than women further down. This is the effect of intersectionality, whereby discrimination and structural inequalities play out in multiple layers depending on where we are situated with respect to ethnicity, class, sexual orientation and gender identity, disability, and other markers of discrimination.

The evidence for this is clear. The labour force participation rate for women in Singapore lags far behind that of men at all ages, and also lags behind that found in other developed economies. Income inequality has increased more significantly within the female workforce as compared to male workers.

The gender wage gap is the greatest in blue-collar occupations, which also have lower wages compared to other occupations. There is also evidence of persistent disparity in wages and labour force participation between different ethnic identities.

Given these, the social engineering of the Marriage and Parenthood Package, amongst other policies, further deepens inequalities between men and women, between women at different levels of the social hierarchy, as well as between people of different ethnic identities. This does not bode well for our vision of an inclusive Singapore.

To arrest the worsening inequality, the State needs to lead the long overdue shift in our social norms by putting an end to the social engineering embedded in its policies. It also needs to recognise that the discourse of “choice” is too simplistic to inform our understanding of how people behave.

To arrest the worsening inequality, the State needs to lead the long overdue shift in our social norms by putting an end to the social engineering embedded in its policies. It also needs to recognise that the discourse of “choice” is too simplistic to inform our understanding of how people behave.

The State’s social engineering is based on outdated and regressive social norms which individual women have had no say in, and yet shape the options that we face. At the same time, individuals and businesses – in their roles as employers, co-workers, spouses or domestic partners and so on – should also recognise that there are many layers of considerations that go into shaping people’s eventual exercise of agency.

It is misleading to pretend that women are fully able to exercise their individual “choices” when, in reality, they are restricted from pursuing alternatives that suit them better than the limited options currently on offer.

Some of these alternatives already exist and are, in fact, not uncommon arrangements. Yet the State evidently denies the reality of these alternatives, treating them as beyond the pale and penalising those who dare follow alternative paths.

The rewarding of those who comply with the “choices” made for them and penalising of those who do not amounts to systematic discrimination.

In commemorating this 101st anniversary of International Women’s Day, let us remind ourselves that this Day came about historically to mark the expansion of women’s choices and rights, including the right to protection against discrimination.

An inclusive society cannot be founded on systematic discrimination, whereby people are herded in one direction after another through carrot-and-stick measures. Rather, an inclusive society should include the range of choices open to individuals and respect the choices they truly make, including choices beyond narrow options offered to them.

References

“Conversation on Women, Babies and Career”, Reach: reaching everyone for active citizenry @ home. 2012.

Ismail, S. 2013. “WoW! Fund to be enhanced”, Channel Newsasia, 12 January, http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/singaporelocalnews/view/1247513/1/.html (accessed 3 March 2013).

Lee, WKM. 2004. “The economic marginality of ethnic minorities: an analysis of ethnic income inequality in Singapore”, Asian Ethinicty, v.5(1), pages 27-41.

Ministry of Manpower, 2000. Occupation Segregation: A Gender Perspective. Singapore: Ministry of Manpower, http://www.mom.gov.sg/Publications/867_op_11.pdf (accessed 3 March 2013).

Ministry of Manpower, 2011. Report on Labour Force in Singapore, 2011. Singapore: Ministry of Manpower, http://www.mom.gov.sg/Documents/statistics-publications/manpower-supply/report-labour-2011/mrsd_2011LabourForce.pdf (accessed 3 March 2013).

Ministry of Manpower, 2011. Report on Wages in Singapore, 2011. Singapore: Ministry of Manpower, http://www.mom.gov.sg/Documents/statistics-publications/wages2011/mrsd_2011ROW.pdf (accessed 3 March 2013).

Mukhopadhaya, P. 2001. “Changing labor-force gender composition and male-female income diversity in Singapore”, Journal of Asian Economics, v.12(4), pages 547-568.

United Nations. No date. History of International Women’s Day, http://www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/iwd/history.html (accessed 3 March 2013)

Wong Pei Chi is an AWARE Board Member. This article was first published in IPS Commons on 8 March 2013. Read the published version here.

The World Health Organisation marks 7 April as World Health Day. The focus this year is on the identification and treatment of high blood pressure (hypertension). Worldwide, figures indicate that above the age of 60, more women than men are likely to suffer from high blood pressure. The reverse is true at younger ages.

The World Health Organisation marks 7 April as World Health Day. The focus this year is on the identification and treatment of high blood pressure (hypertension). Worldwide, figures indicate that above the age of 60, more women than men are likely to suffer from high blood pressure. The reverse is true at younger ages. Is it possible that gender stereotyping leads to social neglect of older women’s health? Is it also possible that some of the older women internalise such gender stereotypes, leading them not to prioritise their own health? When they do choose to attend to their health needs, do they experience any economic hindrance?

Is it possible that gender stereotyping leads to social neglect of older women’s health? Is it also possible that some of the older women internalise such gender stereotypes, leading them not to prioritise their own health? When they do choose to attend to their health needs, do they experience any economic hindrance? Women are often seen as primary caregivers. The Ministry of Manpower reported that 68 percent of women who are not in the workforce identify caregiving responsibilities as the reason for not doing paid work. Consequently, they do not have enough Medisave to fund their healthcare costs, a situation that deters women from seeking medical attention, especially for hypertension, which needs long-term treatment.

Women are often seen as primary caregivers. The Ministry of Manpower reported that 68 percent of women who are not in the workforce identify caregiving responsibilities as the reason for not doing paid work. Consequently, they do not have enough Medisave to fund their healthcare costs, a situation that deters women from seeking medical attention, especially for hypertension, which needs long-term treatment. As Singapore evolves into an increasingly inclusive society, we need to realise our interconnected well-being. No one’s health should be treated as expendable on the basis of age, gender, class, ethnicity or any other marker of difference.

As Singapore evolves into an increasingly inclusive society, we need to realise our interconnected well-being. No one’s health should be treated as expendable on the basis of age, gender, class, ethnicity or any other marker of difference.