By Kokila Annamalai, We Can! Campaign Coordinator. This blog post is written in her personal capacity.

I just finished the book ‘Shame’, which is about forced marriage, honour killings and domestic violence in the South Asian diaspora of Britain. The author is a Sikh woman from Derby who survived very brutal oppression and violence by her family and community, and has spent her life supporting and advocating for other South Asian women and girls in Britain, mostly of Pakistani origin, who’re affected by the same conditions she was in.

I just finished the book ‘Shame’, which is about forced marriage, honour killings and domestic violence in the South Asian diaspora of Britain. The author is a Sikh woman from Derby who survived very brutal oppression and violence by her family and community, and has spent her life supporting and advocating for other South Asian women and girls in Britain, mostly of Pakistani origin, who’re affected by the same conditions she was in.

What struck me about the book, apart from the horrifying experiences of some women, is the author’s evident pride in her South Asian identity, though she consistently refers to the South Asian community – its culture, norms, traditions and practices – as a site of inequality, discrimination and very violent crimes against women.

Like the author, I too identify deeply with South Asia and South Asian culture, especially India. Though I was born in Singapore and have spent most of my life here, my family is from India and has always taught me that India is home. Since I can remember, we went back to India every year for annual holidays. I’ve spent three of my adult years in Tamil Nadu and had quite a few other stints in different parts of India.

I have always loved India dearly, but because of my own experiences and the overpowering narratives of violence and oppression that is the reality of many South Asian women, it is a very difficult relationship – full of contradictions, shame, confusion and even guilt. But the feeling that has been strongest since reading ‘Shame’ is a very personal kind of pain and anger. It’s the same kind of pain and anger I feel every time I read or hear someone say that India is one of the worst countries in the world for women to live, and say it as though it is the most important thing about Indian society, notwithstanding everything else that is beautiful or remarkable about the place or the people.

I get angry not because they’re wrong, overgeneralising or reductionist in their accusations, but because they’re right. I recently came across an organisation called No Country For Women, which fights against gender-based violence in India, and I was taken aback by the truth in that name. It forced me to confront the fact that the love I have for India, at least for now, is unrequited.

Because the place I love is also a place in which I feel very unsafe; because many of the films in my language are deeply misogynistic and promote rape; because when I was sixteen, I was sent away to India where my relatives pretty much kept me under house arrest for six months because I was suspected to be dating a boy in Singapore; because many of the people I worked with in rural India and adore only respect me because I cover up around them and don’t share many parts of who I am or what I believe in with them.

My own community, both here and in India, accepts dowry, tolerates domestic abuse, forces women into marriage, and some people in my family still rebuke women who dare to call their husbands by their name.

Some of the oppressive practices in South Asia have a stronger hold on diasporic communities like mine, which cling on to them as a source of comfort, security and identity in foreign lands; but for me, growing up with other influences, opportunities and identities in Singapore has allowed me to reject those practices and those who impose them on me.

A part of me has always wanted to live in India and contribute to the feminist movement there. And having met my partner there, I’ve had to consider more seriously the possibility of moving there in the next few years to live with him, but I’m finding that it’s such a difficult decision to make. Because of our families (which are conservative), communities (which are punitive), socioeconomic status (not being able to afford the luxuries of private transport makes things even more restrictive and unsafe for women), jobs and other factors, I’m fearful that we cannot live the lives we choose, and that I will be forced to give up some of the things I believe in.

But here is the reality check – these compromises and restrictions are meagre compared to the situation of many women who can’t choose to stay away, who don’t have allies, who can’t support themselves financially, whose rapes and murders don’t make it to the news – hell, they don’t even make it out of their homes – who don’t have the power to reject the oppressive conditions they are in or be heard.

This is the reality check that makes me want to go and not want to go, at the same time.

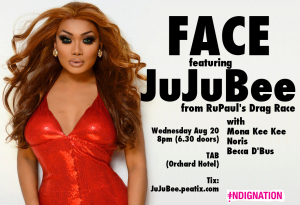

Indignation is proud to present a one night only event featuring JuJuBee from RuPaul’s Drag Race! RuPaul’s Drag Race is the first reality television show starring America’s most glamorous and hottest drag queens.

Indignation is proud to present a one night only event featuring JuJuBee from RuPaul’s Drag Race! RuPaul’s Drag Race is the first reality television show starring America’s most glamorous and hottest drag queens.

I just finished the book ‘Shame’, which is about forced marriage, honour killings and domestic violence in the South Asian diaspora of Britain. The author is a Sikh woman from Derby who survived very brutal oppression and violence by her family and community, and has spent her life supporting and advocating for other South Asian women and girls in Britain, mostly of Pakistani origin, who’re affected by the same conditions she was in.

I just finished the book ‘Shame’, which is about forced marriage, honour killings and domestic violence in the South Asian diaspora of Britain. The author is a Sikh woman from Derby who survived very brutal oppression and violence by her family and community, and has spent her life supporting and advocating for other South Asian women and girls in Britain, mostly of Pakistani origin, who’re affected by the same conditions she was in.