June* is a 49 year-old Filipina and has been living and working in Singapore for 25 years. She was married to a Singaporean man and have two children together. They got divorced in 2008 and June gained custody and sole care and control of the children, who were 13 and 10 years old. After the divorce was finalised, June was informed that she would need to have a Singaporean sponsor for her Long-Term Visit Pass as her children, although Singaporeans themselves, were underage and would not be able to be the sponsor. ICA said she was a “special case” as she was a single mother to underage children and allowed non-family members to sponsor her LTVP until one of her children turns 21 years old. Year after year, June sought help from her Singaporean friends to renew her LTVP so she could continue to work and stay in Singapore with her children. It was a troublesome process as there was no guarantee that she would always be able to find someone to renew her pass.

Access to housing was also an issue for June as a single mother who was also a foreigner. After the divorce, June and her children rented from the private market, spending $700-$800 on monthly rent. In 2015, the landlord decided to sell the house and June and her children suddenly found themselves homeless. They lived with June’s friend for two months but it was not a sustainable arrangement as there was a total of 9 persons living in the 2-room HDB unit. At that point, June was also out of a job. Feeling desperate, she and her children sought help from social service organisations and MCYS, who brought her to HDB to appeal for an HDB rental unit. They have since been living in a rental unit.

In the same year, June also sought help from her MP to get an LTVP+, which would make it easier for her to seek work here*. The MP appeal was successful and June got an LTVP+.

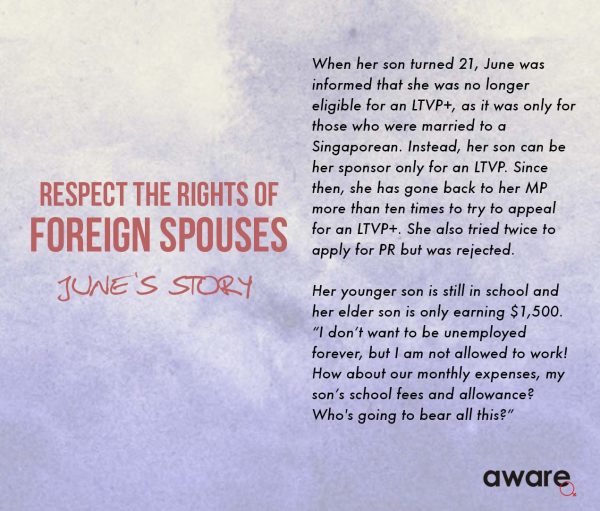

However, when her son turned 21 years old, June was informed that she was no longer eligible for an LTVP+, as it was only for those who were married to a Singaporean. Instead, her son can be her sponsor only for an LTVP. Since then, she has gone back to her MP more than ten times to try to appeal for an LTVP+. She also tried twice to apply for Permanent Residence but was rejected.

Since being back on LTVP, June has been having a very tough time looking for work. When her prospective employers tried to apply for a Work Permit for June, the applications was rejected due to her country of origin (it is likely due to the foreign worker quota). June tried to make an appeal at the Ministry of Manpower and was told that she could try getting her employer to apply for an S-Pass instead. However, the salary amount that employers were willing to pay her were too low given her work experience, and MOM rejected the applications.

June hopes very much to be able to continue working in order to support her family. Her younger son is still schooling and her elder son is only earning $1,500. They are struggling with rent and daily expenses.

“I don’t want to be unemployed forever, but I am not allowed to work! How about our monthly expenses, my son’s school fees and allowance? Who’s going to bear all this? I don’t think that my eldest son can shoulder it all.”

* Prospective employers of those on LTVP+ will apply to the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) for a Letter of Consent (LOC), instead of an Employment/S Pass or Work Permit, for them. LTVP+ holders who are issued with LOCs will not be counted against the foreign worker quota of their employers. Their employers are also not required to pay foreign workers’ levy for them.

On 11 April, AWARE hosted the launch of The Local Rebel’s second zine. The Local Rebel is a Singapore-based collective comprising a group of youths who seek to educate and empower fellow young people on intersectional feminism.

On 11 April, AWARE hosted the launch of The Local Rebel’s second zine. The Local Rebel is a Singapore-based collective comprising a group of youths who seek to educate and empower fellow young people on intersectional feminism.  However, the panelists believe that online activism can be very beneficial in terms of enabling faster, wider communication; many recent rights movements had their beginnings in the online sphere first before moving on to the offline world. Additionally, it can be a good first step for many who are interested in advocacy work. It also helps individuals find their “tribe” or like-minded individuals that can build a supportive community online, which can then precipitate genuine offline relationships. This was illustrated by how many of the panelists and audience members seem to have interacted previously only as internet friends, but have now formed social circles offline as well. Online activism is not only a legitimate form of activism but also a very crucial one especially in this day and age.

However, the panelists believe that online activism can be very beneficial in terms of enabling faster, wider communication; many recent rights movements had their beginnings in the online sphere first before moving on to the offline world. Additionally, it can be a good first step for many who are interested in advocacy work. It also helps individuals find their “tribe” or like-minded individuals that can build a supportive community online, which can then precipitate genuine offline relationships. This was illustrated by how many of the panelists and audience members seem to have interacted previously only as internet friends, but have now formed social circles offline as well. Online activism is not only a legitimate form of activism but also a very crucial one especially in this day and age.

When Tina* was sexually abused by her father, she was in primary school and had thought it was “normal” for fathers and daughters to be physically intimate. “I remember feeling lost and scared. My mother is very proud of the family and I didn’t want to hurt her. I didn’t want to be the cause of breaking the family. I was also scared she would not believe me or blame me. I was scared my father would deny everything, then what could I do? I felt so stuck as a child.”

When Tina* was sexually abused by her father, she was in primary school and had thought it was “normal” for fathers and daughters to be physically intimate. “I remember feeling lost and scared. My mother is very proud of the family and I didn’t want to hurt her. I didn’t want to be the cause of breaking the family. I was also scared she would not believe me or blame me. I was scared my father would deny everything, then what could I do? I felt so stuck as a child.”

Sexual assault can be traumatic and survivors sometimes feel isolated, confused and even unable to get on with their lives. Does it feel like you are the only person going through this? Do you find yourself thinking that what happened was your fault? Or do you worry that family and friends blame you?

Sexual assault can be traumatic and survivors sometimes feel isolated, confused and even unable to get on with their lives. Does it feel like you are the only person going through this? Do you find yourself thinking that what happened was your fault? Or do you worry that family and friends blame you? AWARE’s work – and the work of gender equality advocates everywhere – don’t just end at our own communities or borders. One such instance where we caused ripples of change was last year, when Chinese journalist Sophia Huang Xueqin, visited Singapore to attend a course and bravely spoke out about her experience of being sexually harassed by a senior journalist for the first time. She was subsequently referred to AWARE

AWARE’s work – and the work of gender equality advocates everywhere – don’t just end at our own communities or borders. One such instance where we caused ripples of change was last year, when Chinese journalist Sophia Huang Xueqin, visited Singapore to attend a course and bravely spoke out about her experience of being sexually harassed by a senior journalist for the first time. She was subsequently referred to AWARE