Sobikun Nahar, started Girls’ Night in 2018, where girls who could come together and talk about sexual violence, sexuality, relationships and other topics they find difficult to discuss in their community. The girls would deconstruct incidents that happened to them using applied drama, and act out how they would respond in the future.

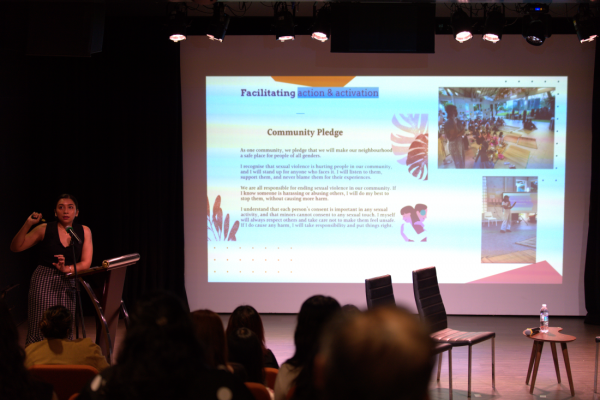

As a community organiser at Beyond Social Services, Sobikun would take the experiences and thoughts that the girls discussed, anonymise them, and share them with people in their neighbourhoods. She’d ask neighbours to sign a pledge, to commit to learning how to create safe spaces in their community.

“Young girls, who are often the most vulnerable and the most at risk of harm, are completely essential to leading the change and are necessary to transform communities,” Sobikun said to the audience.“And often they are the least consulted, the least asked for, and they’re mainly being prescribed solutions.”

Beyond Social Services received 60 signatures from a neighbourhood initiative, and went on to train these neighbours on how to be active bystanders, and how to respond when a neighbour tells them they have experienced sexual assault.

Sobikun said that due to these conversations, girls, who ordinarily would not feel safe talking to boys about abuse or assault, learned that the boys in their neighbourhood would willingly talk about how they can provide support.

“We can’t create a safe space,” Joo Hymn said at the panel. “The issue is how to create as safe a space as humanly possible in a space that is inherently unsafe.”

To tackle this issue, she said the programme must constantly evolve. She takes data from the responses she receives from residential care home clients, from boys, from vulnerable communities, and changes the programme to fit their needs. An interesting note she learned from teaching boys is that male gender expectations to perform prohibit them from being receptive to CSE.

“You’re either alpha or you get pummeled,” Joo Hymn said. The boys felt, “if I ask my girlfriend for consent, she’s going to think I’m damn lame, man. Just get on with it. Who the hell asks for consent in that situation?”

To address these male thoughts and norms, Anupama Kannan from United Women Singapore teaches ‘Boys Empowered,’ a CSE programme tailored to boys and men between 13 and 25 years old. Anupama and her programme team create safe spaces for boys to challenge gender stereotypes, and think about what healthy masculinity looks like.

“We start where the boys are, so we make a little bit of impact with the time we have,” Anupama said. She found it rewarding to see these boys understand why certain gender stereotypes were unhealthy. Yet, like Joo Hymn, she said she is limited by the amount of time she has with each class, and needs to refine the programme to meet these limitations.

Before the panel, IDEVAW 2024 attendees sat in focus group discussions to talk about CSE. In the morning, Devanantthan Tamilselvii, founder of Mental ACT hosted a discussion about how to foster healthy masculinity.

Male attendees talked about how there is a social cost for men when they attempt to be progressive. To break traditional masculine roles is to defy expectations and alienate themselves from their communities.

“I was really interested in hearing from the men on where they get their idea of masculinity,” ZY, an event attendee said.

ZY also attended our improv consent workshop, where instructor Prescott Gaylord taught attendees how to communicate consent. In one of his activities, attendees would engage in ‘Prescott says’ and one attendee would decide to say “no.” When they did, Prescott and the group would give a round of applause.

“Rejection can be a gift,” ZY learned from the exercise. “The person is trusting you enough to state their boundaries.”

Prescott gives all his attendees permission to replicate his training anytime, anywhere. His aim is for people to teach their community members that rejection is okay.

Joo Hymn intends to create and refine CSE programmes for vulnerable girls who have already experienced some form of violence. Before her panel, she hosted a focus group discussion with attendees on how they could create this programme.

Attendees raised that teaching parents CSE may be necessary, as they are the adults that will be responsible for answering their children’s questions. This could be the solution to addressing the time limitations of CSE programmes.

Darren, a Yale-NUS College (YNC) student, was one of the participants who attended the session. He works with Kingfishers for Consent, a YNC CSE programme, and noted that there were individuals from MOE and MSF who shared their opinions during the session. He said he enjoyed “learning more about their approaches to teaching consent in Singapore.”